Muybridge invented his projection device, the Zoöpraxiscope, in summer 1879. This device built on a long global history of interest in image projection dating back to Plato, the Han dynasty and the Ancient Egyptians. However it also extended a strong 19th century interest in the phenomenon of vision itself, which had already resulted in the production of many new projection and moving image devices.

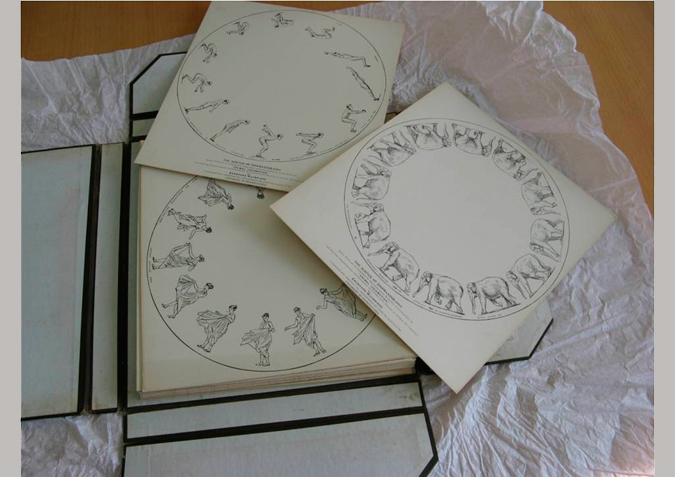

In fact, Muybridge's Zoöpraxiscope served to amalgamate three existing visual technologies popular in the 19th Century: photography, the zoetrope and the magic lantern (Solnit, 2003, p200). Zoetropes (spinning drums) and phenakistiscope (spinning discs) had already produced a sort of pictorial animation, although the resultant moving image could not be projected. Conversely, magic lanterns had been projecting images ever since the 17th Century and had even begun to project photographs. But in this case truly lifelike motion had not been achieved.

What Muybridge did was to borrow the animated illusion of movement from moving image toys and combine this with the capacity for projection embodied in the magic lantern. He then adapted pictures from his motion photography and created a device which for the first time could project sequences of rapid movement informed by the camera onto a screen. To many theorists, the Zoöpraxiscope therefore represents a pivotal moment in the history of the moving image - a missing link between slide projection and cinema.

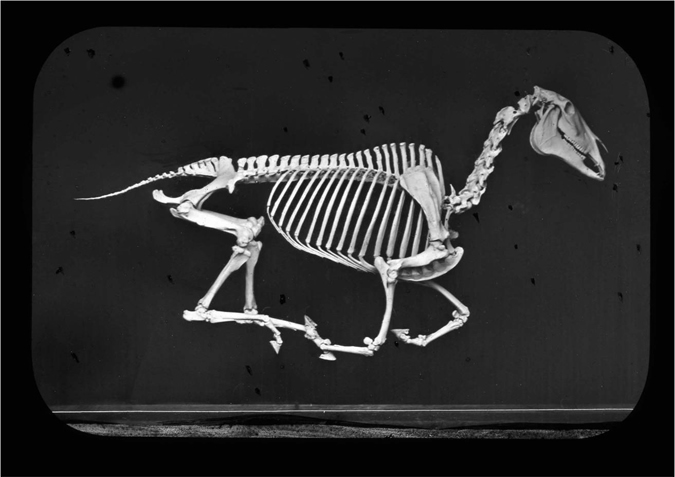

Muybridge generally used painted sequences directly informed by his motion photography for his glass Zoöpraxiscope discs, with monkeys, kangaroos, dancing women, horses and leapfrogging boys variously being animated. However, Muybridge also used at least one set of motion photographs directly for disc images - the horse skeleton pictured above. If Muybridge's painted images anticipate animated film, this photographic disc shows an embryonic photographic cinema.

Muybridge’s favour towards zoopraxography seemed to wax and wane in correlation to public opinion. He used the Zoöpraxiscope to illustrate his lectures for 15 years around the US and on two European tours - entertaining the public, creative professionals and even royalty! However, when his specially built Zoöpraxographical Hall failed to draw crowds at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Muybridge seemingly lost faith in his invention.

After Chicago, Muybridge rarely lectured and by late 1895 had stopped using the Zoöpraxiscope altogether. Furthermore, in a letter dated 1899 Muybridge asked for negatives from of his later Zoöpraxiscope colour cartoon discs to be 'utterly destroyed'. Muybridge did not want to be remembered for this part of his career, feeling that these later discs were a slight on his professional reputation, and too far removed in terms of accuracy from his photographic studies. (Herbert (ed.), 2004 p139)

And the original, acclaimed Zoöpraxiscope presentations not only place Muybridge at the birth of cinema historically, they also reflect an important cultural moment of development in his photographic career surrounding the experience of time within modernity.

Muybridge was grappling with the vicissitudes of modern temporality throughout his career. This theme is visible in his attempts to capture movement, change and identity in his motion studies, and also more subtly in his studies of 'timeless' non-western culture, natural time within landscape, and the fast-paced cultural temporality of the modern urban scene.

What the Zoöpraxiscope represented was an important progression in Muybridge's ongoing representation of motion and time. It reflects the beginning of a paradigm shift in the way modern time was being experienced and negotiated by artist and audience. This was a monumental development only fully realised with the rise of the motion picture film but one which, as ever, Muybridge somehow pre-empted.

Select Bibliography

Hendricks, G. Eadweard Muybridge: The Father of the Motion Picture (London: Secker and Warburg, 1975)

Herbert, S. et. al ed. Eadweard Muybridge: the Kingston Museum Bequest (Hastings, East Sussex : Projection Box / Kingston Museum, c2004.)

Haas, R. B. Muybridge: Man in Motion (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1976)

Solnit, R. Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge. (London: Bloomsbury, 2004)

Introducing Muybridge

Introducing Muybridge Landscape

Landscape The Modern City

The Modern City Transport and Trade

Transport and Trade Foreign Bodies

Foreign Bodies Animal in Motion

Animal in Motion Human Figure in Motion

Human Figure in Motion Zoöpraxography

Zoöpraxography